Why measuring screen time is important

Sometimes there is a disconnection between scientific methods used to investigate a given phenomena and the language used to describe subsequent results.

When it comes to understanding the impact of technology use on health, wellbeing or anything else for that matter, the gulf is vast. See here for a related discussion.

This has become even more important as the UK Government is currently conducting an enquiry around the impact of screen time and social media on young people. The outcome could lead to new guidelines for the public especially parents with young children.

Many academics have already submitted evidence that argues for a cautious approach when developing any new guidance or regulation because the evidence base suggesting any effects (good or bad) remains relatively weak.

However, other voices have concluded that social media and screen time is a public health issue that needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency.

To me, this view ignores the methodological elephant in the room.

The Elephant

In order to argue that social media or smartphone usage is indeed a genuine behavioural addiction and/or a societal problem then the data on which that conclusion should be drawn will need to, at some point, include measures of behaviour.

Research concerning problematic smartphone or social media usage typically relies on correlations derived from estimates or surveys. These measures have some value, but evidence concerning their validity to detect problematic behaviours remains mixed.

It's also worth noting that when correlational designs are scaled up (e.g., when N's become greater than 10,000) self-reported social media use, for example, explains little about a persons' wellbeing.

Collectively, this body of work tells us very little regarding cause and effect.

This methodological gap is particularly frustrating when the very technology we wish to study has the added advantage of being able to accurately record human-computer interactions in real-time. People were quantifying such behaviours in 2011.

In terms of present concerns, longitudinal data of this nature could be linked with other life outcomes, which might include measurements of academic performance, physical and mental health.

Just to be transparent, I have no axe to grind or conflict of interest, but like most scientists, getting to the truth is important.

This will take time, considerable effort and (some) money.

The alternative involves destroying public trust in science by wasting taxpayers' money and indoctrinating people with divisive nonsense.

Current Work

With these issues in mind, my research group often consider how we can encourage other researchers to harness behavioural measures from smartphones. We have developed mobile applications to assist researchers, and analysis routines to process subsequent data.

There is still a long way to go and the rapid pace of technological development makes this even more challenging. It feels like everything moves faster than science. In the time it has taken me to write this Blog, Google have announced new tools to foster digital well-being.

That said, we recently considered how long researchers might need to collect smartphone usage data in order to understand typical patterns of behaviour. In other words, if I check my phone 30 times today, will I do the same tomorrow, in 2 days, or a week later?

Of course, there is nothing to stop us collecting such data indefinitely from a digital device, but this would be ethically questionable.

Therefore, the development of norms regarding the type and volume of data required to make reliable inferences about day-to-day behaviour is important for the field to move forward.

Consistency of Behaviour

Participants had their smartphone usage tracked over a period of 13 days. From this data we were able to calculate the number of total hours usage and the number of checks for each day. Checks are defined as periods of usage lasting less than 15 seconds.

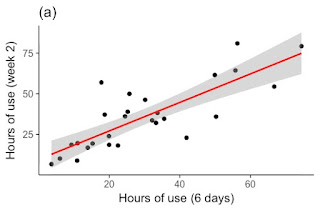

First, we compared the total hours spent using a smartphone between the first and second week of data collection. This generated very large correlation coefficients of .81 and .96 respectively (Figures a and b).

When it comes to understanding the impact of technology use on health, wellbeing or anything else for that matter, the gulf is vast. See here for a related discussion.

This has become even more important as the UK Government is currently conducting an enquiry around the impact of screen time and social media on young people. The outcome could lead to new guidelines for the public especially parents with young children.

Many academics have already submitted evidence that argues for a cautious approach when developing any new guidance or regulation because the evidence base suggesting any effects (good or bad) remains relatively weak.

However, other voices have concluded that social media and screen time is a public health issue that needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency.

To me, this view ignores the methodological elephant in the room.

The Elephant

In order to argue that social media or smartphone usage is indeed a genuine behavioural addiction and/or a societal problem then the data on which that conclusion should be drawn will need to, at some point, include measures of behaviour.

Research concerning problematic smartphone or social media usage typically relies on correlations derived from estimates or surveys. These measures have some value, but evidence concerning their validity to detect problematic behaviours remains mixed.

It's also worth noting that when correlational designs are scaled up (e.g., when N's become greater than 10,000) self-reported social media use, for example, explains little about a persons' wellbeing.

This methodological gap is particularly frustrating when the very technology we wish to study has the added advantage of being able to accurately record human-computer interactions in real-time. People were quantifying such behaviours in 2011.

In terms of present concerns, longitudinal data of this nature could be linked with other life outcomes, which might include measurements of academic performance, physical and mental health.

This will take time, considerable effort and (some) money.

The alternative involves destroying public trust in science by wasting taxpayers' money and indoctrinating people with divisive nonsense.

Current Work

With these issues in mind, my research group often consider how we can encourage other researchers to harness behavioural measures from smartphones. We have developed mobile applications to assist researchers, and analysis routines to process subsequent data.

There is still a long way to go and the rapid pace of technological development makes this even more challenging. It feels like everything moves faster than science. In the time it has taken me to write this Blog, Google have announced new tools to foster digital well-being.

That said, we recently considered how long researchers might need to collect smartphone usage data in order to understand typical patterns of behaviour. In other words, if I check my phone 30 times today, will I do the same tomorrow, in 2 days, or a week later?

Of course, there is nothing to stop us collecting such data indefinitely from a digital device, but this would be ethically questionable.

Therefore, the development of norms regarding the type and volume of data required to make reliable inferences about day-to-day behaviour is important for the field to move forward.

We realised it was possible to consider this in more detail by conducting some additional analysis on an existing data set originally reported by our group here in (2015).

Consistency of Behaviour

Participants had their smartphone usage tracked over a period of 13 days. From this data we were able to calculate the number of total hours usage and the number of checks for each day. Checks are defined as periods of usage lasting less than 15 seconds.

First, we compared the total hours spent using a smartphone between the first and second week of data collection. This generated very large correlation coefficients of .81 and .96 respectively (Figures a and b).

An additional analysis revealed that even 48 hours of data collection alone was highly predictive of future behaviour particularly in relation to checking (usages lasting less than 15 seconds).

Similarly, 5 days of total usage still resulted in remarkably high correlations when compared to a subsequent week. Interestingly, no differences were observed between weekdays and weekends.

So, how much data do you need to determine typical smartphone usage? - not a lot as it happens, but this might vary across different samples. We did however, observe that patterns of usage and checking were more consistent for participants with lower levels of smartphone use overall.

This doesn't completely rule out collecting data for longer periods of time and there are occasions where this might be useful, for example, as part of an intervention to reduce usage or track how these trends might predict subsequent health outcomes. Nevertheless, at this stage we can conclude that even small amounts of usage data can be highly revealing of typical behaviour.

Finally, we observed that self-reported usage derived from the Mobile Phone Problematic Use Scale (MPPUS) remains unreliable when predicting any of these usage behaviours.

Moving Forward

My lab and others continue to develop and refine similar methods and analysis guidelines. We are now running a number of studies which focus on both specific applications usage and the effects of smartphone withdrawal.

Despite results to the contrary, we also remain hopeful that it may be possible to validate some existing self-report scales with patterns and types of usage in the future.

Our hope is that these methods will help answer what have become ever more pressing concerns for society and social science more broadly. That is, what can screen time tell us about people and how might these behaviours lead to positive or negative life outcomes.

I initially became involved with this area of research because it was methodologically and theoretically interesting however, it has now also become politically charged with mixed messages being communicated to the general public.

The discussion has become swamped with celebrities and commentators. Many have good intentions, but these are driven entirely by gut instinct or anecdotal evidence.

Combined with an extremely weak evidence base, these arguments should not drive changes in policy.

Reference

Wilcockson, T. D. W., Ellis, D. A. and Shaw, H. (Epub ahead of print) Determining typical smartphone usage: What data do we need? Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 21, https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/cyber.2017.0652

Comments

Post a Comment